“…Brother Anthony, to whom God gave understanding of the Scriptures and the gift of preaching Christ to the whole world with words sweeter than honey…” (1Cel XVIII; FF 407).

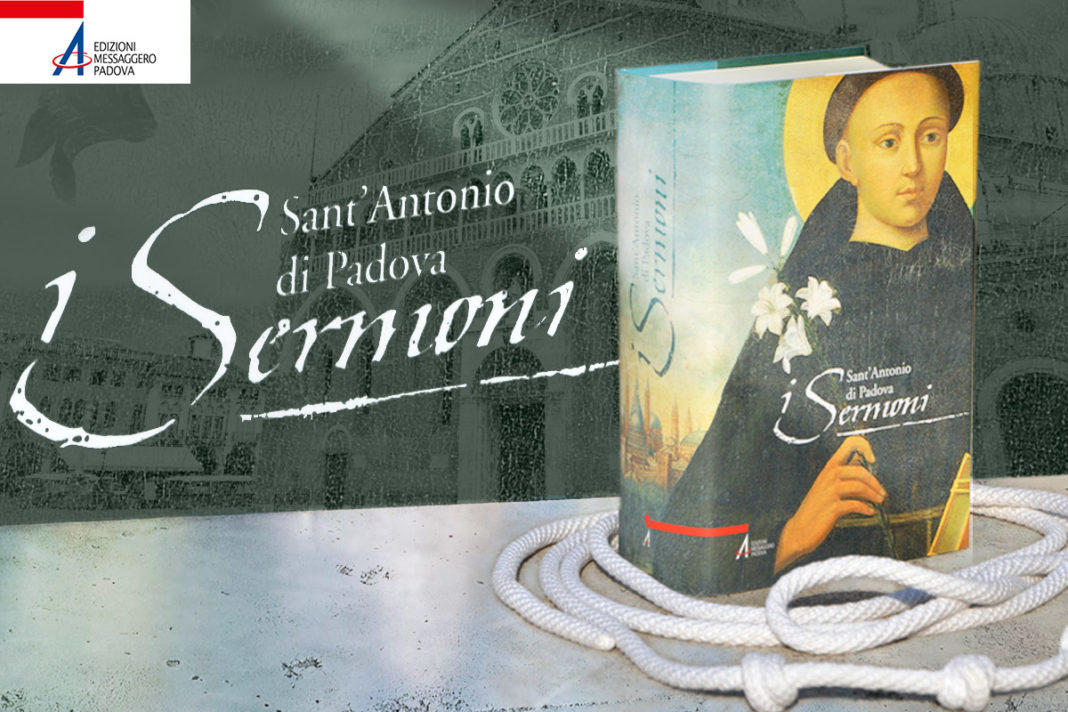

We are nearing the feast of St. Anthony and the 800th anniversary of his entrance into the Friars Minor. Some historians say this took place in the summer of 1220, after the then young Augustinian canon Fernando was deeply moved by the deaths of the Franciscan Protomartyrs who were killed in Morocco. We can retrace some of what Saint Anthony experienced through of the only work of his that has come down to us, namely, his Sermons for Sundays and Feast Days. In them, we can imagine Anthony’s character and his whole being as an Augustinian canon, a friar minor, a magister and a preacher.

As an introduction to this, we should start with the precious note that St. Francis of Assisi wrote to Anthony. It was a happy meeting between Anthony’s intuition and Francis’ discernment. In the note, the Poverello calls Anthony “my bishop” and authorizes him to dedicate himself to teaching theology to the friars by establishing the Study University in Bologna.

The Sermons include some of the lessons that Anthony wrote for the friars who were studying to be preachers. In the prologue, Anthony himself outlines the two purposes that led him to write this extensive commentary on the Word of God, namely, for “the building up of souls and the comfort of the reader and the listener.” The friar from Lisbon had been “conquered by the prayers and love of his brothers” and this constrained him to write the book, though his time was very limited due to his busy ministry as an itinerant preacher. Nevertheless, he somehow found the time to write it during his brief ten years as a friar! He left his confreres an admirable collection of material, especially his Sermons for Sundays and Feast Days. This material was suitable for reaching out to all the varieties of people the friars would meet. Anthony never forgot Francis’ concern—that a preacher should “speak” first through his own testimony; that he should live what he preaches and not engage in arguments or disputes, but be subject to every human creature and be a lesser brother to all.

The Sermons present a novel understanding of evangelization: Anthony turns his gaze to the protagonists, that is, to the preachers and the faithful in need of being reached by the Word of salvation. This focus, and the prayers to the Lord Jesus which conclude each commentary, sets this work apart from others which are purely doctrinal in character. It reveals Anthony’s desire to enkindle a special spirituality in everyone, one that is capable of rising to contemplation. The aim of his work was to break the Word down through teaching, in order to make it comprehensible and usable in one’s life, so that one might be converted to an evangelical life and present one’s heart to Jesus!

When we look at the Sermons, it is not easy to see – or at least we don’t immediately see, how Anthony has applied all his previous formation, formation in service to Franciscan family’s commitment to evangelization. We need to know the cultural, theological and ecclesiastical context of the time. We need a tutorial to help us understand how comments (“glosses”) on Scripture were understood at that time; how theological reasoning and biblical understanding were looked at from four different angles (literal, allegorical, moral and anagogic). In short, we need a basic outline, one which also includes the original way in which Anthony dealt with his sources and conceived of his work. St. Anthony or the “Evangelical Doctor” (Pius XII, January 16, 1946), plays the role of a tutor; in each comment, he indicates what issue he wants to look at and highlights the moral angle of the work because, it is the accepted Word that transforms the conscience and becomes a truly lived experience. Let’s listen to Anthony: “Scripture is the fertile land that yields first the blade of grass, then the ear, then the full grain in the ear.” This dense phrase from the prologue takes its cue from nature. We examine the sacred text from three angles, allegorical, moral and anagogic. These angles are married to three theological virtues. The blade of grass, the allegorical angle, is connected with faith; the ear, the moral angle, is connected with charity; and the grain, the anagogic angle is connected with hope. There is such richness here! However, take courage. With a little patience and some “assisted” reading, we too can delve into the Sermons, a book we should be proud to display in our own personal or Conventual library.

Finally, let’s highlight the similarity between Francis and Anthony’s time and our own, as far as preaching and basic preparation are concerned. The first fraternitas immediately responded to the requests of the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) with a style of witnessing “within” the Church and not “against” her. The Council had proposed the reform of the entire ecclesial fabric starting with the resumption of preaching by bishops and the collaborators they designated. Some dangerous “competition” had arisen in the form of growing heretical movements. These movements had been much more active, more disposed to explaining Scripture in the vernacular, and more attuned to the people’s need for evangelical renewal. It was an easy victory for the heretics: the clergy did not excel in morality, they did not preach and they were not trained.

As for us, we are living in the post-Second Vatican Council period of the “new evangelization” (cf. John Paul II), a time in which we are required, more urgently than ever, to communicate the joy of the Gospel, in whatever language is most suitable, (cf. Pope Francis, Evangelii gaudium). St. Francis exhorts us to communicate this with our own lives secundum formam sancti Evangelii, (the most successful sermon!); St. Anthony follows him, urging us that good preparation is an act of love for the Lord and for the people, as well as an occasion for personal and communal conversion. Then he proposes that we deliver the Word in the Franciscan style: with humble cordiality, without lofty speeches (with a preference for the verbum abbreviatum), by referring to real life (vices and virtues), validating everything by our own lives as joyful Friars Minor (cf. Later Rule, III). Francis’ apparition at the Chapter in Arles, served to “validate” Anthony who was delivering a sermon on the cross to his confreres (the fact is repeatedly reported in the Franciscan sources).

One last insight: a skillful preacher moves his discourse from study to real people. Pope Gregory IX nicknamed St. Anthony the “Ark of the Testament.” We like to think of Anthony as one who was able to go “from the book to the crowd” (cf. Dal Libro alla Folla: Antonio di Padova e il Francescanesimo Medievale by Antonio RIGON [From the Book to the Crowd:Anthony of Padua and Medieval Franciscanism]. We like to think he spoke everyone’s language and that he made himself understandable to all. His pure language is an eloquent sign of how much each of us, by preaching from our own life-works-words, can be a humble and effective minister of the joy of the Gospel. Let us remember the immense appreciation the people still have for us friars, for our closeness to them, for our being friars of the people.

Friar Giovanni VOLTAN