Readings, Commentaries and Depictions

The “custody” of Dante by the Franciscans was about more than the preservation of his bones, which, all in all, remain bound in time and space. The custody of Dante also concerned the preservation of his work.

In 1318, shortly after Dante’s death, the Florentine Friar Accursio Bonfantini, Guardian of the Santa Croce Friary and Inquisitor of Tuscany (1326-1329), held a public reading of the Divine Comedy in the Cathedral of Florence for the city’s ruling lords.

There were several important Minorites who contributed to Dante’s “fortunes.” One of the most noteworthy was Friar Giovanni Bertoldi (1350 or 1360-1445) from Serravalle, a town once ruled by the noble House of Malatesta, which is now located in the Republic of San Marino. Friar Giovanni was the Minister Provincial of Province of the Marches (1405), a great friend of the ruling Malatesta Family of Rimini. It is recorded that while Friar Giovanni was passing through Ravenna (around 1409-1410) he stopped to visit the tomb of the great poet. In 1410, he was appointed Bishop of Fermo, Italy. He participated in the Council of Constance (1414-1418). At the beginning of 1416, during a long pause in the work of the Council, Amedeo Cardinal di Saluzzo and the English Bishops Nicholas Bubwith and Robert Hallam asked him to translate the Divine Comedy into Latin, in order to spread the religious and moral values of the work among the faithful. In just five months, from January to May, 1416, Friar Giovanni completed the translation. It took him from February 1416 to January 1417 to complete his commentary. He did all this while residing in Constance, with few books to support him, relying on his good memory and studies. This request for a Latin translation of the Divine Comedy, even while an important Council was underway, was very significant. It signaled a new, more open era and way of thinking. One should recall that in the 1330s, the reading of Dante’s poem was expressly forbidden in schools for religious. According to the censors of the day, it was a “deadly poison contained in a cup of refined workmanship.” On February 15, 1445, Bertoldi died in Fano, Italy. He had been made the bishop of that town in 1419.

Another important Minorite was Friar Antonio d’Arezzo. In 1428 and 1432, he held Dante readings at the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. We do not know whether he was appointed to do this because of his actual knowledge of Dante’s works or because of his remarkable oratorical skills which must have made him particularly pleasing to the audience. However, we know that on the occasion of these celebrated readings, he had a portrait of Dante painted in the same cathedral with the inscription: “Honor the greatest poet / who is ours, but Ravenna keeps him / because nobody [here] feels pity for him”.[1]

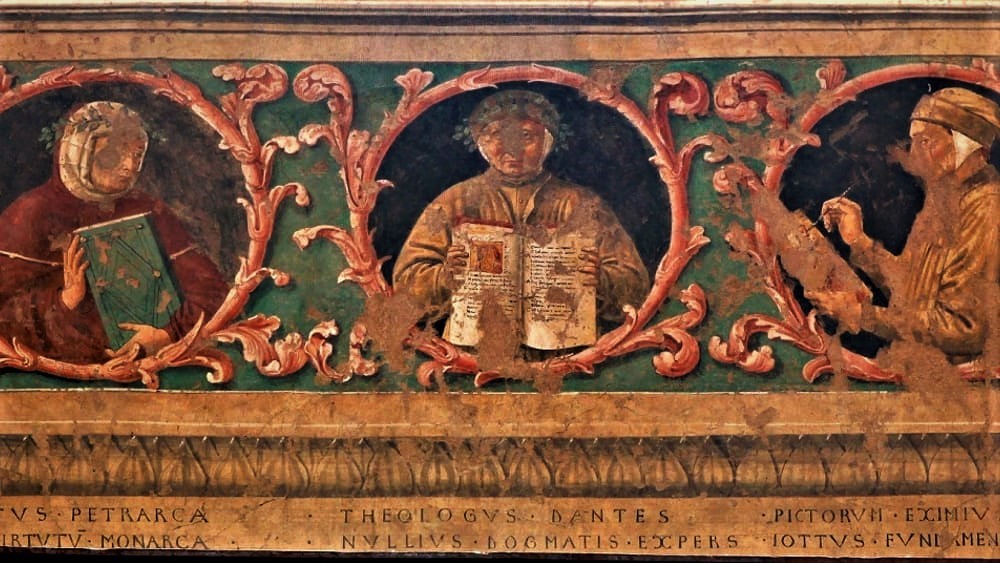

Such pictorial representations helped popularize Dante and his work. Another example occurs in a fresco made by Benozzo Gozzoli in 1452. It is located in the apse of the Church of San Francesco in Montefalco, Italy. The fresco shows stories from the life of St. Francis and was commissioned by the local guardian, Friar Jacopo Macthioli. Immediately above the stalls of the wooden choir, twenty-three roundels were painted depicting the most illustrious doctors and personalities associated with the Minorite Order and the Franciscan Third Order. Just under a large window, a roundel of Dante is flanked by roundels of Petrarch and Giotto. Dante is shown holding a volume of his Divine Comedy open to the beginning of the Inferno. Below the roundel is an inscription which reads: “THEOLOGVS DANTES / NVLLIVS DOGMATIS EXPERS “(Dante theologian, stranger to no knowledge) taken from the opening words of an epitaph for Dante’s tomb in Ravenna composed by Giovanni del Virgilio (who lived between the 13th and 14th centuries).

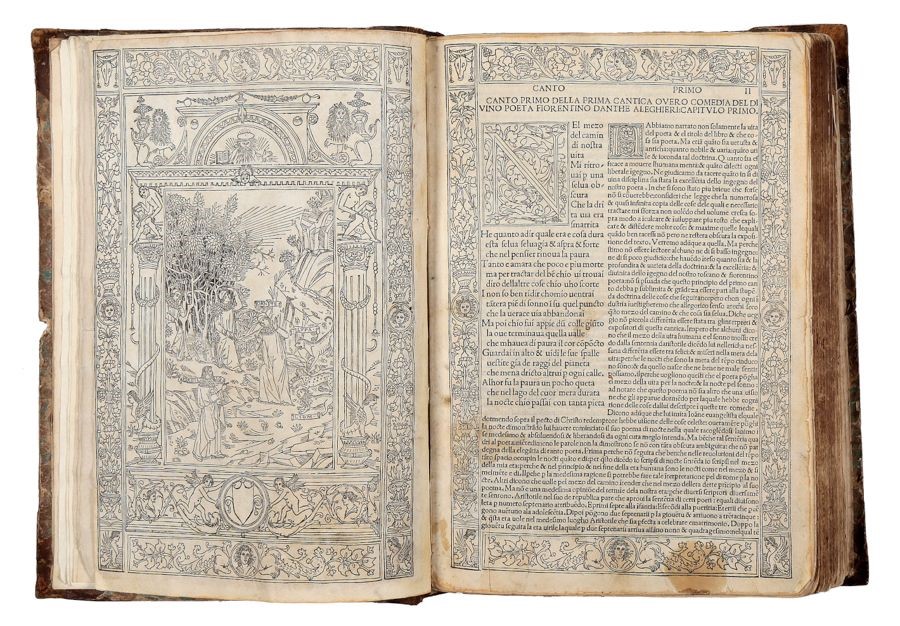

After the invention of the printing press, the Franciscan Pietro da Figino, Vicar General of the Order in 1499, edited four of the fifteen incunabula published of the Divine Comedy. In the 16th century, two editions were produced bearing the inscription “in bibliotheca S. Bernardini”. Two others were produced by Pietro da Figino himself, the second of which, for the first time, was printed with the epithet “divine” on the title page. The epithet became more widely accepted after Giolito used it for his edition in 1555.

Another Franciscan worth mentioning was the Conventual Friar Baldassarre Lombardi da Vimercate (1717-1802). In 1791, he published a commentary on the Divine Comedy which enjoyed great fame and success. It was widely used, even by his critics, and both his Dantean text and his commentary were given the honor of many posthumous reprints. Even if today’s advances in research have somewhat diminished the value of his commentary, in Lombardi’s day, his work was highly praised and sparked genuine interest in Dante’s poem.[2]

There are a few other Conventuals who deserve mention. One is Friar Francesco Villardi of Verona (1781-1833). He composed An Epistle on Dante’s Poem, and A Canticle for Dante’s Christmas Day, published in Verona in 1819. Another notable Conventual was Friar Antonio M. Adragna (1818-1890), who authored a commentary on Dante’s Divine Comedy. His manuscript was lost during the earthquake that destroyed Messina, Sicily, in 1908.

L’Enciclopedia dantesca [Encyclopedia of Dante] also mentions the Conventual Franciscan Friar Stefano Ignudi (1865-1945). He was a pupil of Giacomo Poletto and from 1896 to 1904, served as his substitute for the Dante chair erected by Pope Leo XIII at the University of Apollinare in Rome (today known as the Pontifical Lateran University). Friar Stefano wrote a very extensive commentary on the Divine Comedy (published posthumously in Padua during 1948-1949). His commentary focused on the theological and ascetic aspects of the Divine Comedy and covered a series of Dante’s essays.

We cannot fail to mention in this context, Blessed Gabriele Maria Allegra (1907-1976), of the Friars Minor. He was a student from 1926 to 1929 at the St. Anthony International College on Via Merulana in Rome. The rumor circulated among his classmates that he knew the entire Divine Comedy by heart. Moreover, this was not just some infatuation of his youth, because when he went on to serve as a missionary in China, he continued to dedicate his evenings to reading Dante. From January 1 to December 31, 1965, and from January 1 to December 16, 1967, he composed two books offering daily readings and reflections on Dante. Friar Gabriele Maria Allegra felt close to Dante, both as a Franciscan and out of old personal habit. He loved to recall the familiarity of the Franciscan Order with Dante. He saw this ancient familiarity displayed by St. James of the Marches (1391-1476)—an assiduous reader of the Comedy, and renewed by characters closer to his own times such as the Observant Friar Minor Marcellino from Civezza, born Pietro Vincenzo Ranise (1822-1906), to whom Leo XIII commissioned the important editing of two works found in the Vatican Apostolic Library: the Latin translation and commentary on Dante’s poem by Giovanni da Serravalle and the Italian text and commentary written by Bartolomeo da Colle (Bartolomeo Lippi) during the second half of the 15th century. Friar Gabriele felt that Dante corresponded with the questions in his heart and also with the spiritual needs of the people he met (hence his enthusiastic approval of Costantino Babini who organized a Dante reading for Italian emigrants in France). If Friar Gabriele, like other missionaries, saw being an exile (or advena [being a stranger] as St. Francis recommended), as something at the heart of his own commitment as a Franciscan evangelizer, he could well feel how in sync Dante was with his Order: Dante, exul immeritus [undeserving of exile] and totally dedicated to telling men about God, was someone Friar Gabriele recognized as an excellent Franciscan.[3]

Among the modern-day Franciscans who have loved and disseminated Dante’s work, one should mention Friar Attillio Mellone, OFM (1917-2005). In 1942, he graduated in theology with a thesis entitled: The Doctrine of Dante Alighieri on Creation in General. His passion for Dante culminated in 1971, when he joined forces with the Dante scholar Fernando Salsano to found the Lectura Dantis Metelliana at the San Francesco e Sant’Antonio Friary in Cava de’ Tirreni, Italy. Among other things, they wrote eighteen entries for the Encyclopedia of Dante by Treccani.

Finally, there was the Conventual Franciscan Friar Leone Cicchitto (1887-1972) from Montàgano (Campobasso, Italy), who published several articles in “Miscellanea Franciscana.” These articles were later collected and published in a book entitled, “Postille Bonaventuriano-Dantesche” (Rome, 1940). The book highlighted the doctrinal relations between Dante and the Seraphic Doctor, St. Bonaventure.

[1] Gino Zanotti, La biblioteca del Centro Dantesco in Ravenna. Dai manoscritti alle edizioni del Settecento, Ravenna, Longo, 2001, p. 12, 1416

[2] Ibid. p.13

[3] Gabriele Maria Allegra, Scintille dantesche. Antologia dai diari, edited by Anna Maria Chiavacci Leonardi and Francesco Santi, Bologna, EDB, 2011