4. Characteristics of Religious Orders in His Day

Monastic life gained particular importance in the Middle Ages. It was seen as a kind of exile. Existence in this world was viewed as slavery and a pilgrimage to the “heavenly Jerusalem” with Jesus Christ pointing the way. The very word “world” (in Latin: mundus) was understood in a negative sense by the monastic Orders. The members of these communities saw their vocation as a way to escape the world. Their whole life was aimed at rejecting what the world proposed in order not to be contaminated by it. Distancing oneself from the world, from the City of Babylon, was a way of purify oneself in order to be admitted to the promised land. Such an attitude meant that religious could not perform activities outside the cloister. It made it difficult, or even impossible, for them to reach people who lived in cities.

In addition to religious living in communities, there were also those who wanted to live alone, in hermitages. They were called hermits. They lived their lives at the monasteries, but far enough away so as not to be disturbed. They supported themselves with what they received from the people or what they earned from their own work. Their intention was to resume the lifestyle of the early days of Christianity. Out of this group emerged the “itinerant hermits” who gave instruction to the people who gathered around them. They were something of a rarity in those days, but quite often such movements would lead to the foundation of a monastery. Thus began the Camaldolese, Vallombrosians, Carthusians, and the Cistercians—all founded in the 11th century—with their monasteries built far away from the other monasteries. Their life was a sort of reinterpretation of what St. Benedict proposed in his Rule, which encouraged a life of poverty, filled with prayer and work.

The monks combined “work, detachment and intense prayer with the evangelical life,” but they were not always able to respond to the needs of the society of their time. The monasteries not only became rich, but sometimes when a new monastery was founded, as occurred in England, the local population would be displaced in the name of fidelity to the Rule. The monasteries were known, not only for carefully celebrating the liturgy, but also for welcoming pilgrims, working the land, supporting the state in some of its duties and creating culture. Despite all this, it must be said the monks of the abbeys and monasteries prioritized the spiritual life over other forms of apostolic activity. None of the existing Orders addressed the question of mission in its Rule, or spoke explicitly about apostolic ministry as the mission of the Catholic Church. Furthermore, in the 11th century, apostolic life was seen through the lens of community life; it was not intended as a call to undertake a mission.

Only with time did an approach to the apostolate develop as a commitment proper to religious or to the clergy in general. This apostolate took concrete form in the hospital system, in pastoral ministry and in the field of science. Thus, in the 12th century, in addition to the monastic communities, people began to appear who wished to lead an active religious life. Their ministry included working with the laity, especially the sick and pilgrims. Consequently, in addition to hospital Orders, knightly Orders arrived on the scene, which guaranteed the safety of pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land. Sometimes the earlier hospital Orders were transformed into knightly Orders. Such was the case for the Knights Hospitaller of Jerusalem, the Knights Templar and the Order of St. Lazarus.

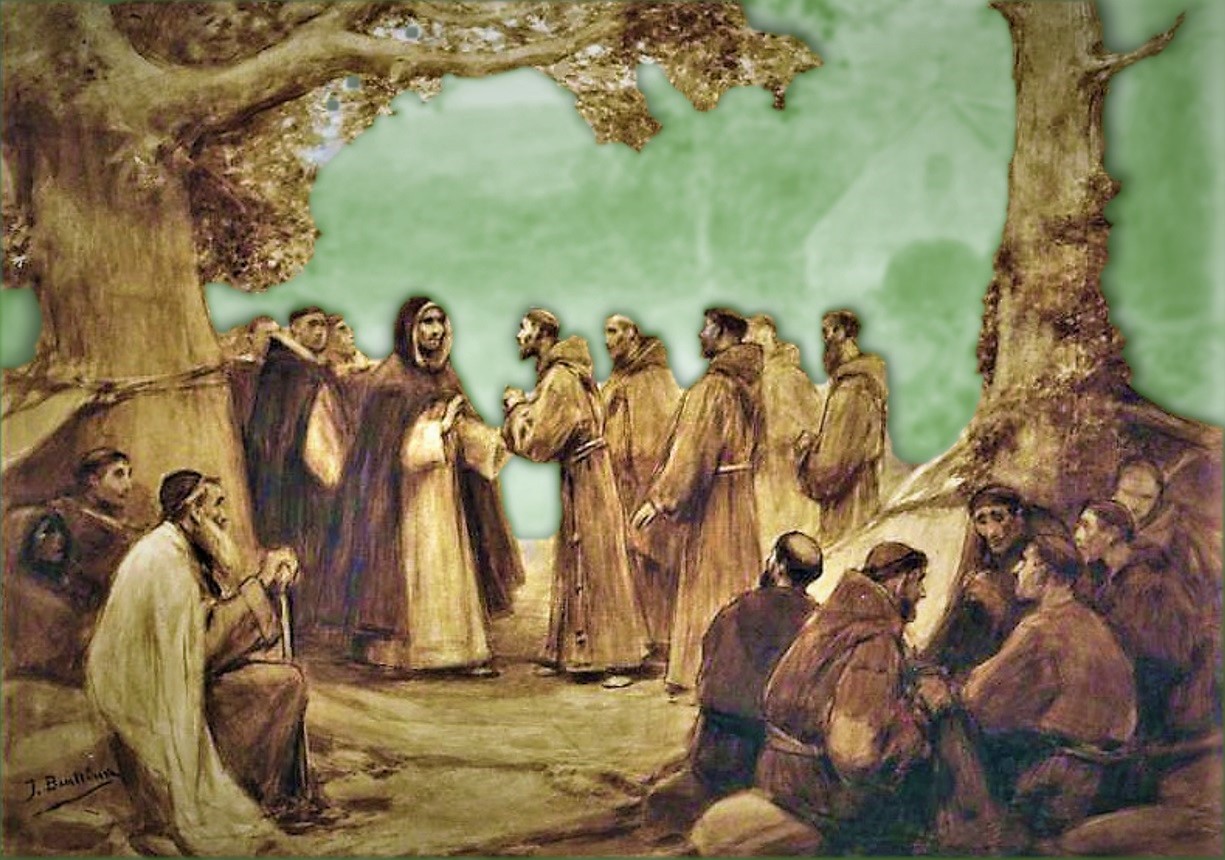

In general, although the 12th and 13th centuries show the clergy performing a variety of vocations, they are presented in a rather polarized light. On the one hand we are dealing with monks who are detached from the world, and on the other, we have the clergy living in the midst of the world with the intention of proclaiming the Gospel. St. Francis, on the other hand, wanted to live in community with his first friars so as to evangelize the world around him. This new style of presence in the world will be discussed in the next article.

Friar Dariusz MAZUREK, General Delegate for Mission Animation

Based upon:

CHÉLINI J., Dzieje religijności w Europie Zachodniej w średniowieczu, Warsaw 1996.

ESSER K., Temas espirituales, Oñate (Guipúzcoa) 1980.

GEMINI A., Franciszkanizm, Warsaw 1988.

KŁOCZOWSKI J., Chrześcijaństwo i historia. Wokół nurtów reformy chrześcijańskiej VIII-XX w. Cracow 1990.

KŁOCZOWSKI J., Wspólnoty chrześcijańskie. Grupy życia wspólnego w chrześcijaństwie zachodnim od starożytności do XV wieku, Cracow 1964.

MICÓ J., Los hermanos vayan por el mundo. El apostolado francisca, SelFr 62 (1992) 213-238.

MISIUREK J., Zarys historii duchowości chrześcijańskiej, Lublin 1992.

URIBE F., „Ir por el mundo” or la evangelización a través del testimio, SelFr 77 (1997) 242-262.

For more information about missions, go to Facebook at:

https://www.facebook.com/AnimazioneFrancescana/

See also the Instagram account of the Mission Secretariat at:

https://www.instagram.com/sgam_ofmconv/