Introduction

Dear confreres, I would like to share some material with you on the missionary vocation of St. Francis. I will describe medieval Europe in general; give a summary of religious life at that time and the situation in non-Christian areas. In this context, I can more clearly show how the Good News penetrated the life of St. Francis and inspired him and the first friars to become missionaries, thus opening a new chapter of mission in the Catholic Church.

Friar Dariusz MAZUREK,

General Delegate for Mission Animation

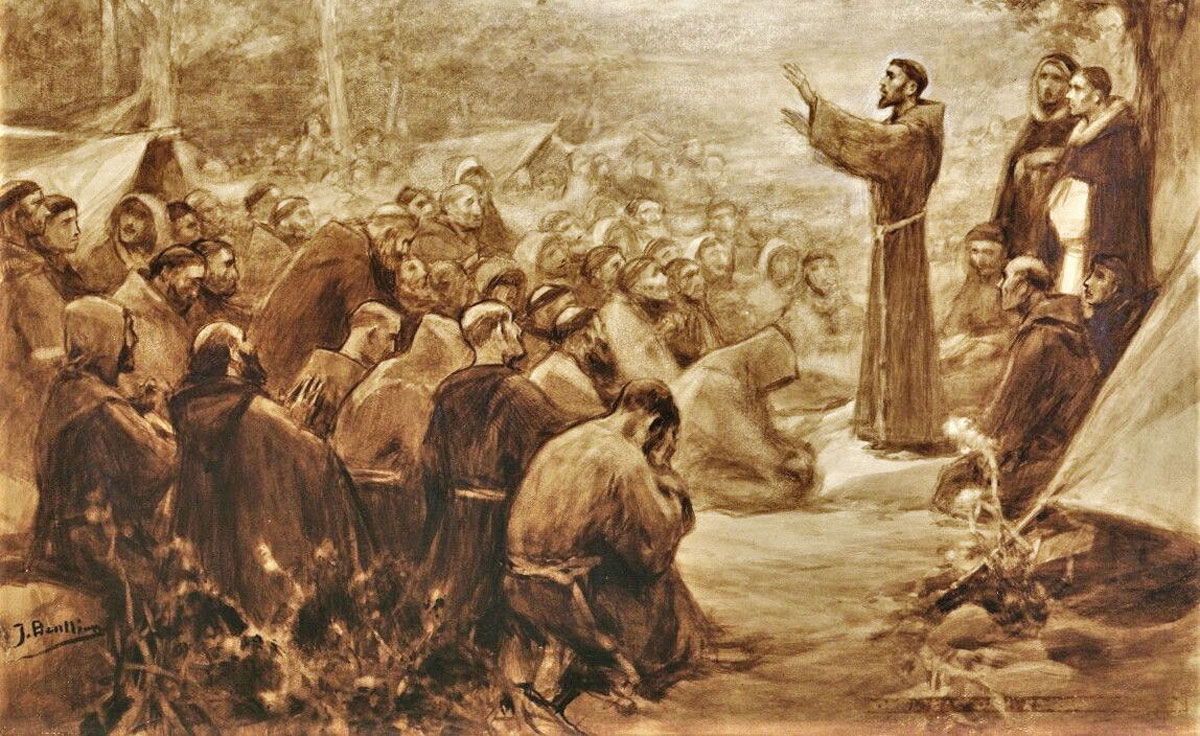

The Mission of St. Francis of Assisi and the First Friars

1. General characteristics of pastoral ministry in St. Francis’ day.

The 13th century was a time when pastoral ministry consisted primarily of administering the sacraments and preaching the Word of God. However, this sacramental service left much to be desired, particularly in large cities that had several churches, since only one of those churches was a parish church. Thus the faithful did not know where to baptize their children.

There was also the thorny issue of judging who had the right to care for the souls of the faithful. When a large number of monks entered the clerical state, that is, when the process of the clericalization of monastic life permitted them to carry out “pastoral ministry,” misunderstandings began to arise between these monks and the diocesan clergy, whose ministry was limited primarily to administering the sacraments. As far as preaching was concerned, one should note that it was primarily the bishops who did it. The pastors, on the other hand, did not so much preach as read evangelical commentaries in order to persuade their listeners to repent.

When God’s people listened to the Gospel, they were faced with the barrier of the Latin language or redundant arguments, which were rather reminiscent of dialectical disputes, because the preachers used words that were too academic. The preached word not only reached the faithful from the mouth of the priests, but also from heretics. It must be remembered that at that time the Church was growing in power and giving a counter-witness in many dimensions, through splendor and riches, among other ways, and all this became nourishment for the protesters.

Yes, there was a great desire to renew life on the model of the primitive Church according to the Gospel, but the heretical groups that emerged at that time, even if they brought together people filled with the desire to imitate the Apostles, declared disobedience to the Roman Church. These groups were the true affliction of the Church, especially since the clergy were not always well educated, and the monks, trained only in the style of stability, were not very capable of facing the challenges of that time. The misdirected zeal of apostolic life, which then embraced not only the clergy but also many lay people, set the laity on the wrong path. Baptism was understood by them as a radical rejection of the world, and the world itself was identified with everything diabolical. The heretics were poor people, that is, they considered themselves as such, and they were very sympathetic to each other and to other poor people. The heretics were roadside preachers, but their doctrine was so divergent from the teaching of the Church, that in the end it was this doctrine that contributed to the recognition of these movements as heretics. By their appearance, they emphasized that in order to evangelize it was not enough to have authority by means of holding a specific office in the Church, one must first experience the Good News personally and only then can one become a witness to it. This was precisely the accusation that heretics made against priests and the hierarchy of the Church.

Faced with this situation, the mendicant Orders of the 13th century were to become an alternative to those other groups and at the same time, a counterweight against the splendor and riches of the Church as well as the new emerging social class, the bourgeoisie, most of whom were absorbed in the desire for wealth. The friaries of the mendicant religious were located in the cities in order to more easily provide pastoral ministry to the people. The mendicants had representatives in the most important universities. They were also involved in defending Christian truths against the aforementioned heretics, preaching among the faithful and spreading the faith among non-believers.

This was the climate in which St. Francis of Assisi appeared. He did not run away; instead, he discovered that he was called to proclaim the Good News as “the herald of the great King”, first with the testimony of his own life and, if the Lord allowed it, also with words. However, this is something we will take this up in future issues.

Based on:

ESSER K., Temas espirituales, Oñate (Guipúzcoa) 1980.

GEMELLI A., Franciszkanizm, Warszawa 1988.

KŁOCZOWSKI J., Chrześcijaństwo i historia. Wokół nurtów reformy chrześcijańskiej VIII – XX wieku, Kraków 1990.

MICÓ J., Los hermanos vayan por el mundo. El apostolado franciscano, SelFr 62 (1992) 213-238.

ORLANDIS J., La Iglesia antigua y medieval, in: Historia de la Iglesia, vol. I, Madrid 1982.

ROCHA M., San Francisco. El profeta de Asís, SelFr 16 (1977) 19-27.

For more information on missions, cf. the Facebook page:

https://www.facebook.com/AnimazioneFrancescana/

Cf. also the Instagram page for the General Secretariat for Missionary Animation:

https://www.instagram.com/sgam_ofmconv/