INFERNO [1]

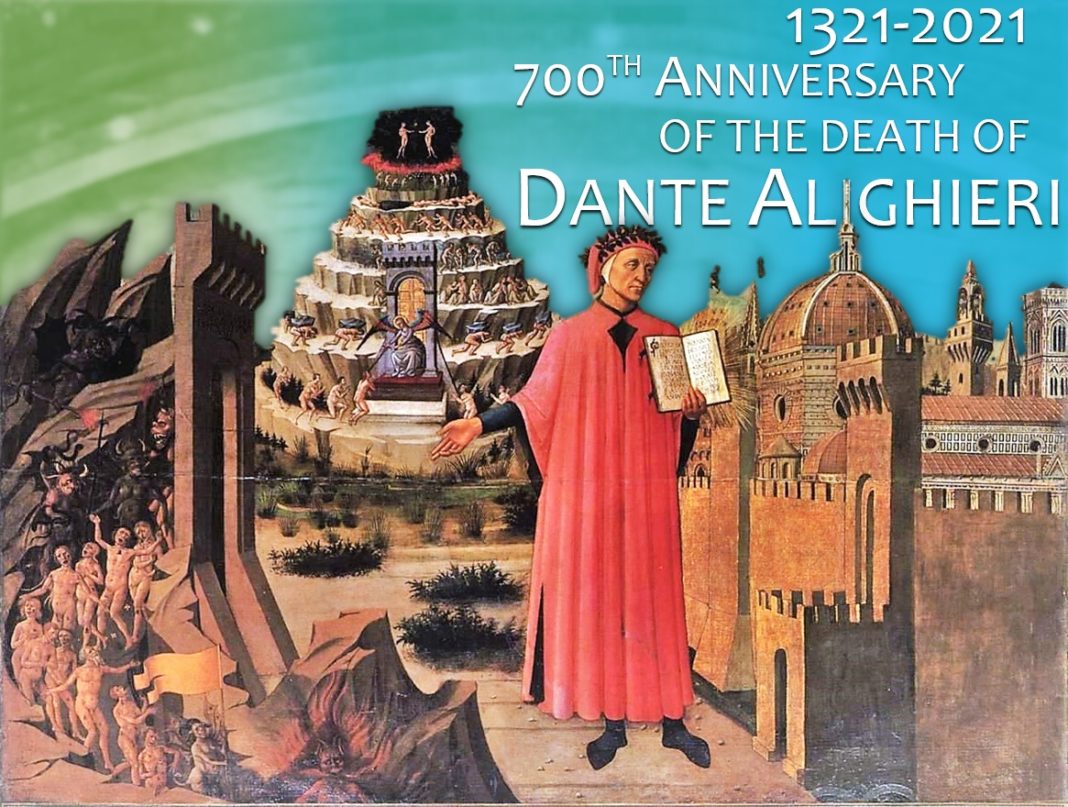

The Christian’s journey into the realms of the afterlife was not a new story in literature. However, Dante’s underworld was something completely different from previous stories. In imagining his journey, Dante created a structure for the afterlife that did not exist before. He gave hell and purgatory precise geographical locations; he placed them on the map of the world. This corresponds with the historical actuality that governs the whole poem. It is told as though it were the story of a real event, a story which travels to real places and thereby involves both geography and history.

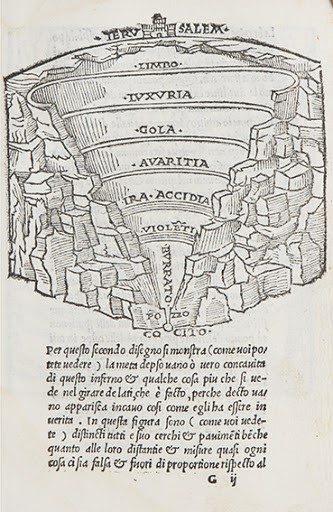

In addition to the historical actuality of geographical locations used in the Divine Comedy, there is also the arrangement of sinners who are grouped following a precise gradation of penalties. Thus we have those who are incontinent, the violent and the fraudulent dividing the infernal abyss into three different regions. The abyss itself is envisioned as a funnel, a circular chasm that narrows as it descends toward the center of the earth where Lucifer is kept.

On a geographical and moral level, this rational structure gives harmony and clarity to the development of Dante’s story. It also gives the narrative character and greater credibility. This is no dream or vision; it is a real journey that Dante intends to describe. In fact, the journey seems so real to the reader, that once, when the poet was passing by some women in Verona, they said to each other: “Look how black he is; he really was in hell”!

As for the manner in which the story is told and the setting of its unknown world, the Divine Comedy was inspired by Virgil’s Aeneid. The distinctive layout of the Aeneid colors the entirety of Dante’s poem. As a whole, the poem retains some of the traditional traits that belong to hell, such as darkness, fire, and tears. However, the various places visited along the way—which are always carefully described, as one might say, from life—are always compared to places on earth that are well known to the readers.

The same comparisons are made with the figure of man, that infernal man who is perhaps Dante’s greatest invention. In fact, man is not a despicable being, entirely negative as was mostly imagined. We must remember that even in hell, God’s love is present, as the writing inscribed above the gateway says: “Justice moved my maker on high: / divine power made me, / supreme wisdom and primal love” (III, 4-6). ). Moreover, man always retains the image of his Creator, a likeness which cannot be taken away from him.

This man preserves his dignity, and his moral conscience (both signs of God’s image). He recognizes his own guilt, and the justice by which he is punished. He is no different from what he was on earth. In a similar way, Capaneus speaks for everyone when he says in canto XIV 52: “What I was alive, I am in death.” This corresponds with a profound theological truth, already defined by Augustine: men in hell are who they wanted to be; they are left with what they chose: themselves; that is, by their own refusal they are deprived of the divine end for which they were destined and thus are deprived of happiness.

Dante’s ability to speak with them, as though he were meeting them on the streets of the world – as happens with his teacher Brunetto Latini in canto XV- is a poetic reality that corresponds with the theological reality.

From this condition arises all the great drama and poetry of the most famous figures in Dante’s Inferno. The tragedy of these people is that their original greatness has now been disfigured; they are reduced to an unhappy existence with no possible redemption. Each retains the value that he or she honored in life: Francesca’s kindness, Pietro’s loyalty, Farinata’s magnanimity and Ulysses passion for knowledge. However, these values are not enough to save them.

From this comes a quality felt through the whole canticle; the form of divine love that is shown in Dante’s Inferno, namely, pity. Pity is deep and heartfelt for the incontinent or the violent. However, this pity lessens when one descends into the deepest region of hell. Here, one enters the world of the fraudulent, where man begins to lose his dignity by using his reason to sin, by using that part of him which is his very identity as a human being. Finally, pity is completely extinguished within the last circle, the icy waste reserved for the traitor. He receives none of God’s pity, since the one who betrays those who trust in him, that is, the one who betrays love, is no longer worthy of the name of man.

This journey has a cathartic meaning and value, namely, purification, both for the poet and for his readers. At each stage, Dante overcomes and leaves behind one of the shackles, or passions, which bound him in his past life. However, such detachment does not happen without pain. This clash of the soul between the old attachment and the new—so evident in some episodes, like that of Francesca or Brunetto or hidden in others, but still present—is what created the profound poetry that has always captivated the readers of the Inferno.

[1] The content of this article is taken from: Dante Alighieri: Commedia – con il commento di Anna Maria Chiavacci Leonardi, Bologna, Zanichelli, 2001, La prima cantica pp. XIX-XXII.